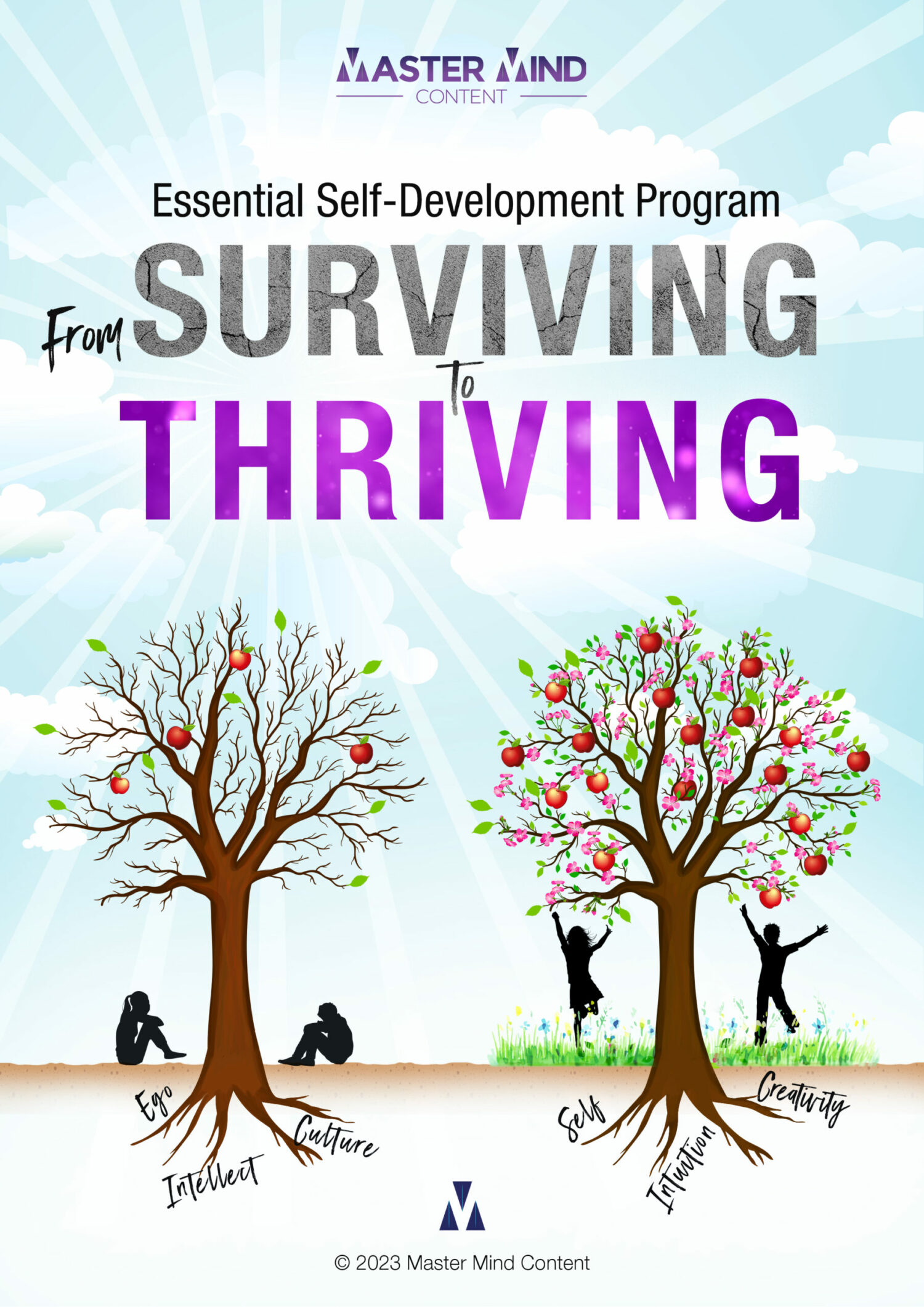

People pursue happiness in many different ways. But the myriad of ways to make you happy can be easily defined in two categories; hedonic and eudaimonic happiness.

Hedonic and eudaimonic happiness are two philosophical concepts that explore different dimensions of well-being and life satisfaction. They represent distinct approaches to understanding what constitutes a fulfilling and meaningful life.

Hedonic happiness is associated with the pursuit of immediate pleasure, joy, and the avoidance of pain. Eudaimonic happiness relates to the pursuit of purpose and meaning.

While hedonic and eudaimonic happiness are often discussed as distinct concepts, they are not necessarily mutually exclusive. There is a strong argument to take an integrated approach. A life well-lived is endowed with both pleasure and purpose.

However, sometimes the latter falls under the radar whilst a hedonistic lifestyle takes precedence. Some individuals can only escape their pain with objects and activities that bring them pleasure.

The pursuit of a purpose in life, on the other hand, can bring about long-term pleasure. That’s not to say you won’t enjoy the small pleasures in life anymore, you just won’t abuse them. Pleasure is an instinctual drive. Purpose is an intentional drive.

Thought-Provoking Quote

“Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation in his life and not a “secondary rationalization” of instinctual drives. This meaning is unique and specific in that it must and can be fulfilled by him alone; only then does it achieve a significance which will satisfy his own will to meaning.”

~ Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search For Meaning [1]

The yardstick to measure the extent of your happiness is how you react and how quickly you recover from disappointment when pleasure is denied.

Let’s take a deeper look.

Hedonic happiness is a subjective experience of positive emotions and the immediate satisfaction of desires. The concept of hedonism, for example, emphasises the pursuit of pleasure and the attainment of enjoyable experiences as the primary goals of life.

Typical hedonic experiences are partying, eating delicious food, sexual intercourse or winning an award. The principal goal is to seek pleasure and gratification through activities that bring about positive emotions such as joy, excitement, satisfaction, and contentment.

The focus of pleasure-seeking behaviour is to maximise positive emotional experiences and minimise negative emotions. And whilst hedonic happiness can be derived from a variety of experiences, the feeling does not last. Once hedonic happiness wears off, you return to your usual emotional state.

Whilst hedonic happiness helps to nurture your sense of well-being, it has to be understood that it only changes your state at the moment. If your typical state leans more towards the unhappy end of the scale, you’re more inclined to indulge in hedonistic experiences more often — and even rely on them to keep you happy.

But what will you do when the things that once made you happy no longer quench your desire?

Thought-Provoking Quote

“Woe to him who saw no more sense in his life, no aim, no purpose, and therefore no point in carrying on.”

~ Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search For Meaning [2]

Studies show that individuals who have no sense of purpose have a higher tendency towards depression and suicide. The researchers concluded a sense of purpose in life has a significant outcome in your well-being, self-efficacy and overall quality of life. [3]

The concept of Eudaimonia can be traced back to ancient Greece. It is a central idea in the ethical philosophy of Aristotle, who extensively explored it in his work “Nicomachean Ethics” in reference to a state of human flourishing, well-being, and fulfilment.

The term Eudaimonia is often translated as “happiness” or “blessedness,” but it encompasses a deeper and more enduring sense of living a virtuous and meaningful life.

Aristotle argued that eudaimonia is achieved through the cultivation and exercise of virtues such as courage, wisdom, justice, and compassion. But virtues must also encompass the realisation and expression of your full human potential.

Thought-Provoking Quote

“Excellence is never an accident. It is always the result of high intention, sincere effort, and intelligent execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives – choice, not chance, determines your destiny.”

~ Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics [4]

This includes intellectual, moral, and social aspects of development. It is not merely about experiencing pleasure but about fulfilling one’s unique capacities at every stage of your life’s journey. You may not be where you want to be yet, but if you take the steps to get there, you will arrive at your destination.

Eudaimonia, therefore, is closely tied to engaging in rational activities that are achievable but push you to learn new skills, character traits and wisdom. Pursuing a life purpose gives you the capacity to reason and broadens your understanding of the world, yourself and others.

Your capacity to understand human nature enables you to make ethical decisions whereby you pursue meaningful goals which contribute to the well-being of the community. This sense of purpose adds depth and significance to life.

Aristotle emphasised the social dimension of eudaimonia. Happiness is not a solitary pursuit but involves positive relationships with others that nurture your self-esteem, confidence and overall well-being.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with seeking pleasure and freedom from emotional pain. Far from it. Hedonic happiness only becomes a problem when instant gratification becomes a habit and a habit becomes an addiction. [Wounded Lover]

Unlike momentary pleasures, eudaimonia is considered an enduring and lasting form of happiness and well-being. The sense of fulfilment that goes beyond transient experiences of pleasure and pain enables you to move away from the need for instant gratification.

Purpose and meaning in life is a personal pursuit which brings you into closer contact with yourself. In this connected emotional state, you don’t feel the need to pursue activities that give you excitement and joy or indulge in food and drink to relieve tension.

Eudaimonia brings hedonic happiness into equilibrium. It enables you to create healthy attachments to your external world because your passion and fulfilment are satisfied by engaging in activities that give your life purpose and meaning.

Hedonic adaptation allows you to engage in fleeting pleasures. This kind of enjoyment can improve mood during the day, even though you know your happiness is temporary.

It can also be the case that individuals with low self-esteem vehemently pursue their purpose and deny themselves pleasure. People who are devoted to religious practices of abstinence, for example, forgo immediate pleasure in the pursuit of the life purpose they have chosen.

You may also find this in people who are workaholics [Wounded Everyman] and martyrs [Wounded Caretaker]. If you see your sense of purpose is in the servitude of others, you might deny yourself the hedonic pleasures you need to nurture your well-being.

In both cases above, the motivation to give yourself over to a higher purpose may be to seek recognition and appreciation, or, in the case of spiritual pursuits, to put your life back on track.

However, abstaining from pleasures because you believe they are sinful could result in denying yourself the opportunity to enjoy life and find happiness. [Lover]

Finding a purpose that gives your life meaning can be a game-changer. But you shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the small pleasures in life prove that you’re worth it.

Thought-Provoking Quote

“I view my life as being abundant with meaning and purpose. The attitude that I adopted on that fateful day has become my personal credo for life: I broke my neck, it didn’t break me. I am currently enrolled in my first psychology course in college. I believe that my handicap will only enhance my ability to help others. I know that without the suffering, the growth that I have achieved would have been impossible.”

~ Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search For Meaning [?]

[1] Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search For Meaning, p.121 (1946)

[2] Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search For Meaning, p.98 (1946)

[4] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethic

[5] Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search For Meaning, p.172 (1946)